The Carvings

Traditional artists, who strove for excellence in order to please the spirit world, understood that harmony is the balance of Spirit and Physical elements. The saying ‘plait the rope that binds the past to the future’ has guided the creation of the carvings which take inspiration from old art to retain its essence and to honour its ancestry.

Several carvings feature birds inspired by Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū. This ancient carving style used notched profile face stylisations, probably to represent ancestors, and these have been adopted in the reconstruction of these treasures.

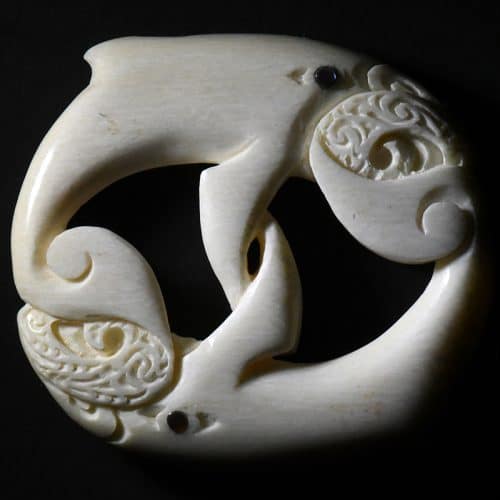

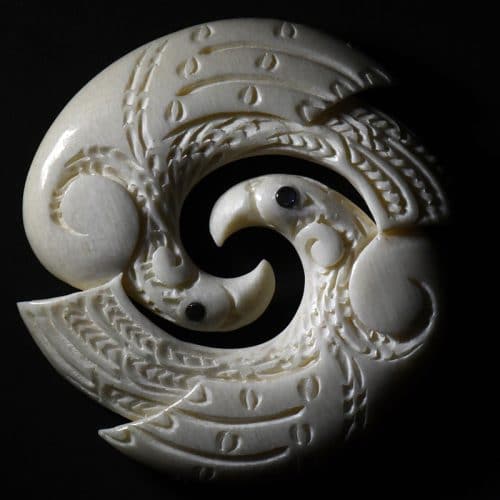

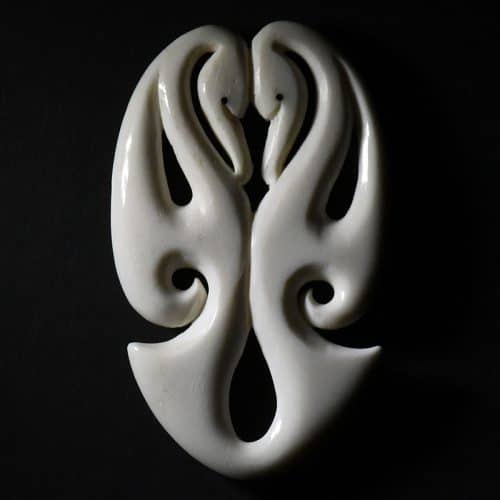

In some carvings, the faces use the manaia, a form which is derived from the profile, half of a stylised human figure or often just its face. The concept is that all creation is composed of two complementary opposites, Ira Atua and Ira Tangata, or Spirit Life Force and Physical Life Force and our stylised profiles thus represent our two halves.

As all of creation can be personified and shares the same spirit, the stylised human derived profile or manaia can represent the spirit of anything in creation. In their various physical appearances, manaia therefore have unlimited possible uses and have developed to represent both spirit and physical aspects.

Some birds have their wings depicted as hands with fingers to convey their recognition as ‘bird people’, just as we are ‘human people’. Similarly some of the whale flippers are shown as ‘hands’.

With the carved pendants, the bone represents the physical whilst the cut outs represent the spirit aspects. When worn, others see through these cut-out areas to the wearer, who becomes an integral part of the spirit of the design. The pleasing shapes of the cut outs are therefore a vital part of the design.

The balance of plain and textured surfaces also convey this concept.

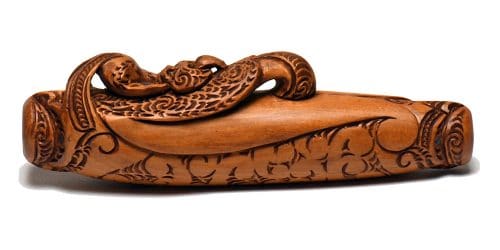

Bone has always been a special medium for Māori artists and whilst these days bones such as moa and human are substituted, three items in the exhibition use niho parāoa, sperm whale teeth. These have come from the iwi of Mōhua where the whales stranded. Such strandings are seen as gifts from Tangaroa, and carving them is a way of honouring that gift.

The first mention of pūmoana or pūtātara in ancient mythology is when two of them were blown to signal the success of the god Tāne in his mission to ascend to the topmost heaven and obtain the baskets of knowledge necessary for survival on the earth. They are still used for announcing special events when they are blown like a trumpet. These were so special that people would recognise the identity of an approaching visitor by the sound of the pūtatara. Most of the old instruments were small heavy shells. Occasionally the large triton shells like this one were washed up to become very special treasures. A later legend tells how a mysterious song heard by fishermen came from one of these shellfish as it retreated to safety when hauled aboard clinging to a net. This taonga has a double face on the mouthpiece which represents its male trumpeting voice and the female crying sound of Hine Mokemoke, the ‘Lonesome Maiden’. It also reflects the significance of joining a shell from the sea god’s realm with the wood from the forest god’s as a symbolic peace truce between them. Seabird feathers dangling from the end, complement the traditional adornment of this taonga.

Karanga Manu - Pīwaiwaka

This bird call represents the friendly and cheerful sounding little fantail, which sometimes in tradition is likened to a warrior dancing around as if challenging us to catch it. These bird calls were brought back to life when Richard Nunns, a member of Haumanu, a group dedicated to the revival of traditional Māori instrumental music, found a stone one in the collection of the National Museum of New Zealand, now called Te Papa Tongawera. He put it to his lips and immediately assured the custodians that it was indeed correctly labeled. That original one was made from soapstone but these tiny ones made from mataī are a charming substitute.

Karanga Manu - Riroriro

There are several instruments which also create quiet, private sounds like Raukatauri and this is one. Some of these can also become beautiful and functional pendants and this one, carved from mataī is a stylisation of a riroriro, or grey warbler. Originally, the purpose of this tiny flute was to lure birds by mimicking their own calls, sometimes to come into the hunter’s range for easy capture. By placing the pursed lips at the correct angle to the mouthpiece and blowing, the player is able to mimic several kinds of bird calls. Today this little flute can create interesting and humorous responses from garden birds and forest dwellers alike. Then as we reflect on these beautiful sounds we can create our own bird-inspired songs. The mataī karanga manu is treated with an organic oil enhanced with a mixture of traditional kōkōwai, or ochre.

Karanga Manu - Weka Whakatoi

In the Hall of Mankind of the British Museum lies a small soapstone carving like a nguru but with only the one finger hole at its upturned end. It was a great surprise to this researcher when he put it to his lips and heard the distinctive weka call that cheekily echoed from it so far from home. From replicas of that first soapstone remnant we find they can also be played as a melodic instrument or be used to add weka’s vocal colour to a song. By flicking the finger off the end hole while blowing, the cheeky call of the weka is produced. By manipulating the size of the end hole with your finger it also becomes a charming flute. To communicate with weka the dimensions may need to be changed to suit local conditions as trials show that weka have dialects which require different pitches of instruments in order to elicit a response. These communication calls have been likened to cell phone rings.

Nguru - Iho Maire

This nguru adapts the traditional exterior shape to make it fit in with the series of karanga manu and weka. It does have the same interior shape and though nguru are generally smaller than kōauau they have four functional wenewene or finger holes. This one is carved from maire which is a very special wood, treasured by Māori. Its hardness makes it very suitable for nguru and it is an ideal wood to use for depicting a kōkako - we can see it’s a kōkako because of the rounded tail and wattles.

Nguru - Kairaki Ngaro

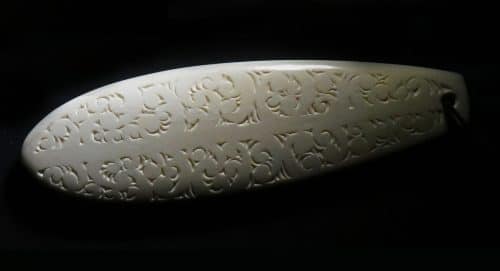

This nguru has the name Hidden Songsters because hidden in the song pattern on the body of the flute are songbirds shaped in the ancient rock painting style. A wooden nguru in Te Papa Tongawera has a small poi or flax ball attached to it which fits snuggly into the mouth of the flute. We found that sometimes wooden nguru, because of their enclosed design sometimes stop singing after a while but a quick wipe of the inside bore quickly restores their voice.

Nguru - Te Niho Reka

Despite the difficulty of making a nguru from such hard material as this whale tooth, especially with ancient tools, many have survived and are in museum collections. It is no wonder that they are prized taonga. Their hardness and density also gives them esteemed musical qualities and it also means that they do not get their song fogged with condensation like wooden ones sometimes do. This sweet sounding tooth is carved as the parāoa or sperm whale from which it came many years ago.

Nguru - I Te Ao Hou

This nguru has its larger blown end carved to represent the face of the instrument. The two South Island kōkako carved on the underside, have come to the sound of the song carved on the nguru. They are carved in the ancient style of the whale tooth kākā carving from Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū, Banks Peninsula. They epitomise the importance of keeping the essence of ancient traditions alive in today’s world. The patterning on the body of the nguru represents the music going out to the world and making pleasing shapes in the silence.

Nguru - Kōpere

Underneath this small nguru is korimako who has heard its sound and has come looking for Raukatauri to listen and learn her wondrous song. His design is inspired by the bird on an ancient whale tooth carving from the central South Island though the wings are depicted as hands to show that he is a ‘bird person’. This nguru has been slightly modified to become easily played from the upturned end with the breath of the nose. The dawn chorus of a mass of these birds is reflected in its name, which refers to that carillon like sound and also to its rapid flight.

Kōauau - Pepe Hani

This kōauau has a male moth carved on the

underside reminding us that when he hears the amazing sound of Raukatauri singing he must come to be with her. He is carved as a ‘moth person’ with antennae, which like heru or hair ornaments, help us to identify him as a moth. His arms rise up past his head and his hands flatten out becoming stylised wings. With the koru at the bottom signifying the wonderful gift of flight they have been given. The slightly bulging shape of kōauau represents the tūngoungou or case of the casemoths. This shaping is often used as an acknowledgement of the importance of these ‘houses’.

Kōauau - Reka Tonu

This kōauau has its larger blown end carved to represent the face of the instrument. The lips, nose and eyes are carved around the open mouth through which it is played. When playing, the instrument’s nose is brought close to the player’s as in the traditional Māori hongi, or greeting where breath is shared. The other end is carved in a similar way, but with two noses as this is the face of the music, which is created by the breaths of the player and of the kōauau. Kōkako is carved on the underside of this kōauau having mistaken its song for that of Raukatauri who he has come to eat in order to enrich his song. Like him the kōauau amplifies parts of her song which we also treasure.

Kōauau - Tōpū Tūī

Kōauau have several traditional functions from assisting in childbirth, to healing broken bones and mourning the departed. They also are used for transmitting history through songs and for songs which entertain where they act as a kīnaki or embellishment to the song. Along the sides are a pair of tūī who have heard the song and come to listen and learn then try to imitate it. Their design is inspired by a bird on an ancient whale tooth carving from the central South Island though the wings are depicted as hands to show that they are ‘bird people’. The patterning on the body of this kōauau, which is carved from ancient swamp mataī, represents the music going out to the world and making pleasing shapes in the silence.

Kōauau - Korimako Tōpū

Figures on the ends of this kōauau represent a pair of korimako or bellbirds with their large hands representing their wings. The patterning on the body of this flute is adapted from the taowaru design to represent the flowering kōwhai tree, which provides delicious nectar, a favourite food of bellbirds, tui and other birds. Along the sides are two rows of manaia-style faces representing the traditions of passing the songs and tunes through the generations. This kōauau is carved from ostrich bone which has very similar shape and size to the moa leg bones of long ago. Though human bones traditionally were known as making the most cherished songs, these and emu bones make an acceptable substitute.

Kōauau - Tipua Moana

Blue whales are the largest beings known to have lived on Earth, and are some of the eldest children of Takaroa, the Sea God. Their songs travel through the great oceans so well that recently a study group of scientists set their hydrophones out in the west of Te Ara a Kewa (Foveaux Strait), picked up their song, and then followed it down to Antarctica to learn more about them. This piece is carved from a large wapiti leg bone and features flippers carved as giant hands to remind us that he is a ‘whale person’ and indeed the bones within these flippers are like gigantic human hand bones.

Pūtōrino - Whānau Kākā

This pūtōrino is carved to tell the story of Raukatauri, goddess of flute music, and it takes the shape of the cocoon she lives in. The face which adorns the centre hole is the face of Raukatauri singing to attract her mate. The tiny face at the end is the face of the music, with two noses showing that the music is created by combining the breaths of taonga and player. The three figures carved above the face of Raukatauri represent the three families of kākā, kākāpō and kākāriki.

It was a thrill when Hirini Melbourne called a kākā which landed in a tree just above us. Then he and Richard played several taonga puoro and after each the kākā replied with a different song of his own. I had no idea they had such a repertoire - Brian Flintoff

The surface designs on the instrument represent the music creating pleasing sounds in the silence and uses similar designs in four fields to represent Ngā Hau e Whā, the four winds, a traditional saying representing people from around the world. The bindings are split cane which tightens on drying .

Pūtōrino - Kōkako

This pūtōrino features Raukatauri, goddess of flute music, and it takes the shape of the cocoon she lives in. Her face, shown singing to attract her mate adorns the centre hole.

The manaia face represents a kōkako who has heard her song and arrived to eat her and further sweeten his song. The tiny face at the end is the face of the music, with two noses showing that the music is created by combining the breaths of taonga and player.

The instrument is carved from ancient, swamp-preserved, native mataī and coated with special oils enhanced with traditional kōkōwai or ochre. The bindings are split cane which tightens on drying.

Pōrutu - Ngaro i te Rangi

The body of this flute is covered with a design which depicts the music flowing out into the world and making pleasing shapes in the silence. This design is created in four adjoining fields to represent the traditional saying, Ngā Hau e Whā, the four winds, a saying to represent all people including those from far away. Here it also symbolically encompasses ‘people’ from times far away or hidden in the contemporary kōwhaiwhai style surface carvings. There are twenty bird people and other beings engraved in rock art type stylisation. Pairs of tūī, riroriro, kororā, pūkeko, kōkako, korimako, pūtakitaki, kākāpō, pīwaiwaka, and tohora are hidden. Pōrutu are versatile instruments and their ability to play in two octaves and also jump up to another octave was, and still is, a prized facility.

Pōrutu - Nā te Pō ki te Ao Hou

This pōrutu celebrates the joining of the ancient with the world being shaped now. The taniwha Ngārarahuarau, who came in the waka Huruhuru Manu, left behind scales shed in his death throes after being tricked and then burned. These were said to lie waiting to give rise to new taniwha. This image is inspired by the ancient rock art to represent that idea and so stands on this contemporary pōrutu to remind us of the truths hidden in these mythical stories, for indeed such shape shifting taniwha still thrive. Fortunately the pleasing music we see carved on this instrument has obviously placated this monster, which is typical of the power of these pōrutu, as told in legendary stories where players were able to mesmerise even a hostile audience sometimes allowing the player to make their escape and join their beloved.

Pōrutu - Tōpū Kōkako

The pōrutu is a flute from the family of Raukatauri and is similar to a kōauau but is longer and has the finger holes toward the far end. It has the ability to be overblown giving it a second and sometimes a third register. Around the open mouth of the blown end, the face of the instrument, a kōkako pair is depicted. The face of the music surrounds the other end and this has two noses to remind us that the music is the combination of the breath of the player and the breath of the pōrutu. The finger holes are represented as faces to depict Mauī Mua, Mauī Roto and Mauī Taha whose names are sometimes used for these wenewene (finger holes) and who are immortalised as the three stars of ‘Orion’s Belt’. Above either end is a stylised manaia face representing a pair of kōkako who have come to the song of the pōrutu hoping to find Raukatauri to eat and thus sweeten their own song.

Pūmotomoto - Te Hekenga

The pūmotomoto is a flute from the family of Raukatauri and has just one finger hole toward the far end. Traditionally it had a special function and was played while the words of tradition were also chanted through it. This was done to implant tribal lore into infants while their fontanelle was still open.

This pūmotomoto tells some of the stories of Māori instrumental music. The face of the instrument with two noses representing the concept that music is the combined breaths of player and instrument, is carved around the lower end. Tāne is depicted with two birds, kōtuku and hākuwai who accompanied him on his climb to the twelfth heaven to obtain the ‘Kete Mātauranga’, the baskets of knowledge. Opposing them are the hordes of sandflies, mosquitoes and bats sent by Whiro to try and stop him. The body of the flute is covered with a design which depicts the music flowing out into the world and creating pleasing shapes in the silence. Both instrument and stand are carved from recycled native mataī.

Pūkāea - Kōkako

This is a small pūkāea or trumpet. These were traditionally used to send warnings and messages and also to make announcements to the locals or to the gods to obtain their blessing on what was happening, be it a birth or the planting of crops. The face at the blown end represents that of the instrument. The large face on the end is adapted from the myth of kōkako, a bird which was given the secret of singing as beautifully as Raukatauri, the goddess of flute music. She loved her flute so much that she changed herself into a casemoth and lives within that pūtōrino like case. Kōkako eat casemoths and thus not only gains her voice but also amplifies it so that we can all hear it. This is a young bird but still with the ability to throw a sound directionally and loudly. This pūkāea is carved from a recycled mataī verandah post. Its binding is rattan cane, an aerial root which shrinks tight on drying and adds a special quality to the sound. It replaces the traditional split kiekie aerial root which is now not as available.

Pūrerehua - Whānau Ngārara

Pūrerehua are children from the family of Tāwhirmātea, the wind god, and as the winds have no visible body they are ‘spirit children’. These instruments try to emulate their sounds and therefore they also share that esteem. In a Southern story they also had a practical purpose and then were named ‘Hamumu Ira Garara’ for the sound that entices the lizards from their hiding. The carving on this one depicts a family of lizards attracted by the sounds they sense which resembles the fluttering of a big juicy moth or pūrerehua. It comes with a handle which makes its use less stressful for the user. This is adorned with a small effigy representing Tāne the father of trees and many living things.

Pūrerehua - Ngā Hau e Whā

The pūrerehua is like similar instruments found in many cultures and its common stature as a child’s play-thing belies its traditional status. Its urgent chant was used for spiritual purposes and some were famed as rain callers, with the player’s own life force deemed to be travelling along the cord to disperse their thoughts to the four winds. This Pūrerehua is carved from beef bone. It is played by swinging it around above the head after giving it a twist to set it spinning as it is launched. The pattern is an acknowledgement of the wind songs it creates as the sounds make shapes in the silence. The design is done in four sections representing Ngā Hau e Whā, the four winds, a traditional saying which includes people from all places. The plain and carved areas also represent the complementary concepts of Ira, the Life Force, Ira Atua, the Spiritual and Ira Tangata, the Physical.

Porotiti - Tai Uta

The porotiti is usually an oval disc with a cord going through two off-centre holes. It is played by looping the cord around the hands then twirling it a little to start it spinning. By applying alternate pressure then relaxing the cord each time the disc untwines, a hum is created. Then by carefully blowing gently on its vanes, it starts to sing and create its own songs. One naming has them as kōrorohua when just spinning, changing to kōrerohua when being blown on. By varying the breath, new rhythms can be created. Porotiti are used as ‘songcatchers’ where the player listens to this kōrero to set rhythm for the composition of mōteatea, songs. They were also used as accompaniment to karakia, or prayers. This one is carved from bone. The designs represent Ngā Hau e Whā, the four winds, which carry the wishes of the player to the world.

Porotiti - Kōparapara

Porotiti create ultrasounds and vibrations and they were used by old people to ease arthritis pains. Playing them over the faces and chests of sleeping children helped clear the mucus from their sinuses. They are one of several instruments which create quiet, private sounds like Raukatauri and can also become beautiful, functional pendants. Porotiti are children from the family of Tāwhirimātea, the wind god, and as the winds have no visible body they are ‘spirit children’, these instruments try to emulate their sounds and therefore they also share that esteem. This one, carved from a knot of mataī, features a rapidly flying kōpara, or female bellbird because the sound of their fast beating wings is similar to her being twirled gently.

Rei Niho - Kahukura Uenuku

This carving depicts Kahukura Uenuku the Māori God who has the special function of looking after the Earth Mother, Papa tu a Uenuku or Papatūānuku. His colourful manifestations are as kahukura, the red admiral butterfly and as Uenuku, the rainbow. These are both represented here with the red admiral form represented on this side as a ‘butterfly person’ and distinguished by antennae.

Because the caterpillar of the red admiral eats only nettle it has become endangered by our wish to keep stinging things away, usually by using various toxic methods which also reach the soil. This piece is therefore a reminder of the wisdom of this god and his messages and a reminder that we can assist and hopefully somewhere find space to plant some nettle.

On the other side he is seen as the spirit of Uenuku with the rainbow’s colours represented by the up stretched fingers and down pointing toes. Traditionally an image of Uenuku was kept near the garden to ensure the health of the soil was protected. Sometimes an image of him was taken when on the warpath to assist with divining.

Rainbows are carefully observed as they can be tohu or signs to help people make the correct choices or decisions.

This representation is carved from niho parāoa, the tooth of a sperm whale which came ashore on Onetahua, Farewell Spit and was named Whaowhia.

In its display case it hovers over a healthy-looking depiction of a māra where some green ongaonga, or nettle grows.

The original ancient, but now incomplete, carving which inspired this has been a marvel to me for many years, the remaining detail, its shapes and its flowing form indicate awesome skills, even more so when one considers the tools available to its creator. I also wondered what story it told. It had come from Te Pātaka o Rakaihautū, Banks Peninsula and is now in Canterbury Museum under the guardianship of Te Rūnaka o Koukourārata. This version pays respect to its creators and owners and honours the ideas it conveys to enrich our world. When I received a suitable niho parāoa or sperm whale tooth to do my imagined version of it, I waited more years while I thought of a story which would explain my version. Reading the book Kākāpō by Alison Balance I decided a current story would be fitting so I carved the bird as Felix the male kākāpō who has sired so many chicks in the kākāpō recovery programme - Brian Flintoff

The line of upward curves represent his great booming calls and the serrations along the top are the high-pitched directional sounds he makes. The stylised face profiles along the bottom represent some of his ancestors, and the ones along the sides represent his mates and some of his progeny. The carving is nestled in an old piece of driftwood which washed up on the beach near my driveway.

Hei - Te Ata

The enormous toroa spend most of their lives gliding over the wave crests on motionless wings seldom even meeting their relations. For this carving, toroa views his reflection in the waters of a very calm day when he has to use his wings more often. While the sounds of albatross cries are not music to most other beings, when these great birds come back to land at their nesting sites and greet their mates, the rhythmic clapping of their bills punctuated with a variety of gentle vocalisations is quite memorable. That their eyes appear to be crying makes their homecoming so special that it is captured in traditional sayings, song and art.

Hei - Kaiwawara

These tiny, delightful birds which tend to arrive in small flocks to our gardens in winter are usually noticed first by their gentle flocking calls as they clean up insects or sip nectar from kōwhai and other flowers. However, like several taonga puoro, they also have quiet songs. These are heard when they are alone and sound like a blackbird whispering, so much so that for years I just thought that I was hearing a blackbird in the distance. It is a delicate song that is well worth listening for. This one is carved as both the flocking member and as the singer.

Hei - Ngākau Mōhio

Korimako are exquisite birds both in looks and song. Sadly their massed singing of a dawn chorus like a chiming of bells is seldom heard now. But it is from this that their English name is derived. In Māori oratory it is a huge compliment to liken some-one to a bellbird, either for their beauty, oratory or fine singing. In this carving, korimako sees her reflection as she flies over a pond but in her heart knows that she is a ‘wahine korimako’ or ‘bellbird person’ with a song that quickens the listener’s heart.

Hei - Whakarahi Tuatahi

Kōkako, or the blue-wattled crow, is the world’s purest-noted songbird. This attribute was gained in mythological times after kōkako did a favour for the demigod Māui, who granted him decorative wattles and told him the secret of song was to eat Raukatauri, the casemoth and goddess of flute music. Thus he became the first amplifier and lets us hear her beautiful song which other songbirds, like the tūī and bellbird, also try to copy. The sometimes organ-like song of kōkako is the most haunting sound and is truly unforgettable when heard in the forest. When not being worn, these kaitiaki, carved from kōiwi parāoa, (sperm whale bone), become an interesting conversation piece in their nest carved from native mataī.

Hei - Te Hongi Aroha

To see the majestic white heron, the kōtuku, is a sight to make your spirits soar. Its regal posture and pure colour reflect its status as the most sacred bird of Aotearoa. This is reflected in a famous saying, He Kōtuku Rerenga Tahi, the bird of a single flight. For some it is a magnificent sight seen only once in a lifetime. Kōtuku also command a very special place in Māori lore as a spirit messenger. Kōtuku and Hākuwai were the guardian birds who accompanied Tāne on his climb to seek the kete of knowledge from Io. Thus they are a kaitiaki for people who are also special. Here they are reaffirming their bonds on returning to Okarito for the next breeding season.

Hei - Kā Kaitiaki Whenua

Myth tells how the South Island was created from the waka of Aoraki and its crew who were turned to stone after their waka rolled onto its side after striking a reef in a great storm. Atua, descendants of Rangi and Papa, under the leadership of Takaroa and Tū te Raki Whānoa, were given the task of making it a suitable habitation for people. Since then these two, in the form of humpback whales, swim around our shores to keep a watch on their handiwork. Humpbacks are awesome singers sometimes coming together to join in their song cycle which travels vast distances through the ocean. These songs when speeded up are in stanzas that sound much like that of a blackbird.

Hei - Kanikani Aroha

As well as having such special songs that even the other songbirds keep trying to emulate, kākā have a very special pair bond, probably lasting for life. This is seen as mutual feeding and in their mating dance. Sometimes, from a perch in a tree, the male dances with wings flapping and tail fanned while singing. They often sing while feeding and when one breaks the song to catch an insect or eat a berry, the other will continue the song. Here they are carved with the male dancing around the female in a courtship display.